“Total” is a good word. Whether or not you like Arnold Schwarznegger movies. Whether or not you’re a Valley Girl.

“Total” is a good word. Whether or not you like Arnold Schwarznegger movies. Whether or not you’re a Valley Girl.

“Total” conveys a sense of comprehensiveness. Like you’ve thought of everything.

It’s the main reason that “Total Cost of Ownership” is part of our business vocabulary. Don’t get me wrong; the other words in TCO matter. “Cost” is a number we all want to know. “Ownership” gets us to think about the economics of operating something and disposing of it in addition to the economics of acquiring it. But “Total” gives the answer its authority. A TCO analysis is a complete analysis.

At least that’s the theory.

When the Gartner Group propagated TCO as a central element of high tech product analysis in the 80’s, it was a big step forward. It took the analysis of purchasing decisions beyond simple price comparisons. A sensible comparison of alternatives should involve understanding the differences in operating costs, including: installation, training, services, maintenance, labor and logistics. Beyond that, there are timing questions that are introduced to a good TCO analysis, including: the timing of payments, an understanding of product life and a product’s trade-in value.

But TCO has its challenges as a method for quantifying and communicating value to a customer making a purchasing decision. When robotically deployed, TCO can miss key sources of value and blur the focus of a value proposition.

There are several methods for quantifying and communicating value to a customer making a purchasing decision. Alternative approaches include TCO, ROI and EVE®. If you are careful in how you use them, they all get to the same answer. But there are differences in emphasis and in practice, resulting in strengths and weaknesses of each. Thinking in terms of customer math, some first principles and some sound practices can be a useful reference point for comparison.

TCO Strengths

As a practical method, TCO has three essential strengths:

- Clear organization: It should be no surprise that engineers like TCO. Not to stereotype, but engineers tend to think in matrices. The starting point for any TCO analysis is to list the products being compared across the page as columns, list the types of cost and the technical parameters that contribute to those costs down the page as lines and start filling in the cells. In practice, the types of cost often get standardized once several product teams have started to do this for their product and their customers. Cost lines in a TCO matrix often include acquisition costs, disposal costs, installation, training, services, maintenance, labor and logistics. This standardization means TCO can become an embedded process fairly readily, at least for technically oriented product teams with this 2-dimensional matrix as the place to start. Having numbers from a previous example comparison can help teams get underway. Adding a third dimension, time, tends to stretch the limits of intuitive matrix thinking and may not be part of a standardized framework, but that two dimensional matrix template often provides a strong framework for a common approach.

- Clear unit of measure. Clear organization tends to force a clear unit of measure. Frequently, the unit of measure is a time period. Making the unit of measure per year or over the life of the product makes answers translatable into the language of finance. Annual TCO analyses frequently bear a strong resemblance to good pro forma analyses. An alternative, and very useful, unit of measure for B2B companies is per unit of their customer’s output. This is a good choice when translating a value proposition for a product used in a production process into simple operating metrics that will resonate with a customer. Pre-determined units of measure can help simplify the process of quantification. When product teams don’t have to make choices, they often get started faster. This helps embed TCO analysis as a routine process or discipline.

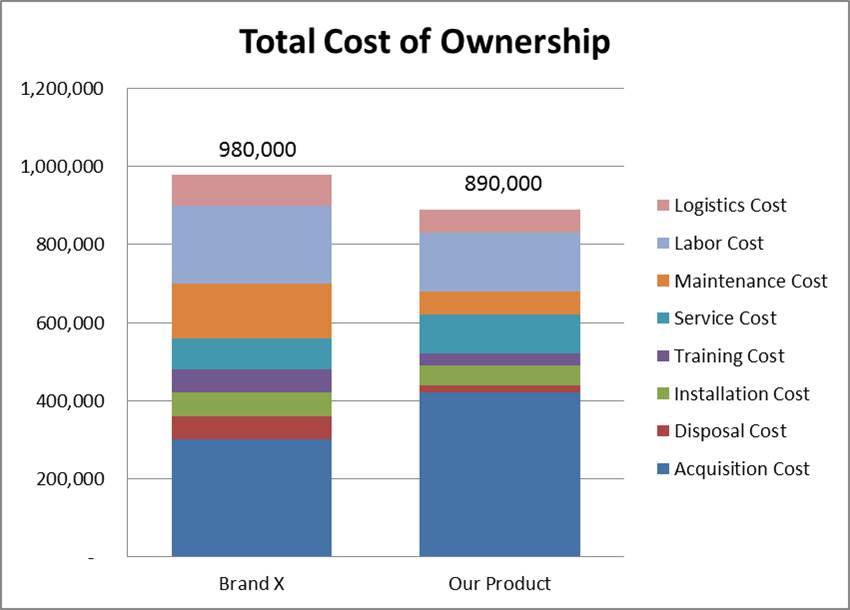

- Clear bottom-line communication. A single number to make a compelling case that your product is better is the hallmark of good TCO analysis. “Our product will save you $300,000 relative to Brand X.” A short, clear declarative statement helps when you are talking to someone with a short attention span. It goes well on a summary slide. It can lift a conversation out of the weeds. And it is often conveyed in a style similar to a weight loss commercial: “Brand X has a TCO of $800,000; our product’s TCO is $500,000.” Having a single number that applies to each alternative also makes a TCO approach work effectively when there are several alternative competitors that are potentially part of a customer’s decision process. If a new competitor suddenly pops up into a customer conversation, the answer can be crisp if the TCO analysis is well prepared.

TCO Pitfalls

There are also aspects of TCO analysis that present challenges in building a strong value proposition. With clear thinking they can all be addressed. But getting it right takes care and attention to avoid the pitfalls. Here are three questions that help identify and address the challenges of TCO:

- Are you communicating your differentiation effectively? TCO, as usually presented, highlights Total Costs, not where they come from. The reason that engineers like TCO is the same reason that marketing people tend not to like it. The job of marketing is to provide powerful messages about how your product is better. Once the benefits of a product are clearly articulated, it is natural to ask what each of your points of differentiation is worth to your customer relative to a competitor. In a classic TCO presentation, the important points of differentiation and their comparative economics are often buried in two value stacks. To highlight your differentiating features and quantify what they are worth takes extra work. The work isn’t hard for someone good at spreadsheets, but a TCO analysis is incomplete if it stops with the summary answer from the template that just says how much better your product is in Total. Product management teams need to take the next step. If their product is quantitatively better, they need to articulate why it is better, communicate that differentiation and quantify what each key element of differentiation is worth.

- Does your TCO analysis include too much irrelevant information? There is some downside in setting the objective of an analysis as one of estimating “Total” Costs. Some, perhaps many, of the items in your totals may be irrelevant to your customer in making a decision between your product and a competitor. But the matrix discipline is often dominant in practice and these irrelevant items are laid out in the TCO presentation almost out of necessity, given the claim that the costs are “Total.” The problem is that these irrelevant items are elements of your customer’s business. This means that your customers will have views about them. Irrelevant information invites discussion and debate that have nothing to do with your key messages and that have nothing to do with a customer’s decision for or against your product. Setting yourself up for tangential discussions, leaving yourself open to irrelevant challenges, is a recipe for distraction and ineffective conversations.

- Does your TCO analysis highlight all your important sources of value? The problem is that TCO deployed in a value proposition may not articulate your product’s “Total” Value. TCO analyzes product costs but usually misses product benefits.Unfortunately, there is a vocabulary problem masked in “TCO.” In common parlance, “Cost” is only one measurable element of what matters to your customer. Your customer cares about Revenues and Risk as well.

If you don’t think so, then you aren’t talking to the C-suite. The language of Enlightened Economists (not an oxymoron, believe it or not) would extend the notion of “Cost” to “Opportunity Cost.” Opportunity Cost is notionally very broad and would legitimately include estimates of your product’s impact on all aspects of your customer’s business, including revenue and risk. But business people, no matter how well trained, are not necessarily fluent in Economics-speak. This means that TCO, as usually applied and as generally templated, has a built-in bias in favor of estimating expected, ordinary costs and a bias against assessing a product’s impact on a customer’s revenue or including a product’s impact on low probability, possibly high consequence, customer risks.Estimating the impact of your product on customer revenue or customer risk rarely comes easily. And figuring out how to talk about revenue or risk can be a daunting task if you somehow are suggesting that your estimates are “Total.” As before, the claim of “Total” has its downside. But articulating how your product improves revenue and reduces risk can provide powerful value messages. Leaving revenue and risk out of your value proposition can be like a vow to use your fists in a gunfight. Especially if part of your marketing and sales challenge is to provide persuasive reasons for your customer’s higher level stakeholders to buy your product. Articulating revenue and risk value messages can help close more deals at a higher price.

In sum, TCO can be a useful B2B framework or discipline, but the best TCO results come from (1) applying TCO creatively beyond Costs as usually defined and (2) directing your Cost discussions to the Costs that matter to your customer’s decision. The point of a quantitative value proposition is to highlight the math you want your customer to focus on in making that decision.

Organizations looking to make customer math central to their approach to product management, marketing and sales almost always start with spreadsheets. But dueling spreadsheets can cause confusion. Spreadsheets don’t usually provide a common framework. They don’t build fluency in a common language understandable by the customer.

To embed customer math work in your organization, you need a scalable platform:

- A clear framework

- Designed to articulate the primary ways your product is better

- Easy to follow

- Easy to use

- Easy to avoid mistakes

- Easy to change units of measure to translate effectively for different stakeholders

- Consistent graphics and messages that others can understand and use

- Customized but QA’ed materials to leave behind

A scalable cloud platform drives effective, tailored customer value propositions that quantify differentiation and improve value capture.

Click here to request a 15-minute demo of LeveragePoint

About Peyton Marshall

Peyton Marshall is CEO of LeveragePoint. Previously, he served as CFO and Acting CEO at PanacosPharmaceuticals, Inc., CFO of EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and as CFO of The Medicines Company through their initial public offering and the commercial launch of Angiomax®. Previously, he was an investment banker in London at Union Bank of Switzerland, and at Goldman Sachs where he was head of European product development. He has served on the faculty in the Economics Department at Vanderbilt University. Dr. Marshall holds an AB in Economics from Davidson College and a PhD in Economics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.