Coaching Experienced Players. Good value coaches help colleagues quantify the differentiated value of our offerings for better go-to-market strategies, improved pricing, and superior sales performance. Some of our colleagues are new to value management. Their coaching needs are usually clear: basic skills, play design, drills, and practice, often in the context of getting to useful content fast.

More experienced players generally have greater immediate potential. They are often more self-assured. Frequently they have good habits and strong motivation, but they may not be open to constructive criticism. Working with these players is both rewarding and challenging for any coach.

Previously, we drew parallels between coaching soccer in the three phases of the game and coaching commercial teams in the three stages of value management and value selling. Quantifying value is like playing midfield. Designing Value Propositions requires the skills of a good back or keeper. Teams selling value need to be effective strikers.

So far, in this series on coaching midfielders to quantify value, we have outlined how to frame the discussion, how to focus on customer-centric differentiation, how to dollarize positive and negative value drivers and how to make apples to apples price comparisons. Good coaching questions help to move less experienced players along, improving the way they play midfield.

More experienced players can always improve their game. But coaching them is different. We start by observing their play. Then we identify two or three elements of their game that they can work on. Ideally we pick the elements of their game that will have the greatest immediate impact. In coaching experienced midfielders to quantify value, the process invariably starts by looking at, or “proofreading,” their value models, to identify potential issues, and to improve value content. Motivated players “always want more.” Like Lionel Messi, they are “never satisfied.”

In contrast, undermotivated players sometimes need to be incentivized. We should have them present their models to a live audience, potentially their management. Often, it is only by stumbling as they present, or by fumbling questions, that they realize they need to improve.

Proofreading: Two Levels of Coaching. Constructive value coaches can proofread a model in ten to twenty minutes by identifying two kinds of issues:

Proofreading: Two Levels of Coaching. Constructive value coaches can proofread a model in ten to twenty minutes by identifying two kinds of issues:

- Mistakes, based on how comparisons are framed, how value is calculated, and how changes and customization of the model can be made to reflect customer specifics;

- Gaps, where there is nothing wrong with the math or the analysis, but where the value model could be filled in to become more useful in segmentation, pricing, offering design, and value discussions with customers.

Even experienced professionals make math and spreadsheet mistakes. Good value coaches point out these mistakes diplomatically. “I was looking at this calculation and I might have done it differently.” “I am not sure I understand this formula. Can you walk me through it?”

Gaps in a model present opportunities to make models stronger and to build out segmentation effectively. “I was thinking about how to validate this assumption. Have you considered…?” “Let’s see…, we have compared our gold offering to the competitor. How does the math change if we look at our silver offering instead?” “That revenue value driver works if our customer is capacity constrained. Is there other value they might realize if they have excess capacity?”

By judiciously mixing questions to spot mistakes and questions to identify gaps, a good coach can help a team member improve their content in a diplomatic way that limits player resentment and maximizes player motivation.

Four Steps to Proofread a Value Model. There are four steps good coaches take to identify mistakes and gaps:

- Look at how the model frames comparisons, including customer segment(s), our offering(s), and reference alternatives, whether competing offering(s) or the status quo;

- Review how units are set up and utilized to make appropriate calculations and comparisons;

- Consider how value drivers and prices are calculated, and in what customer circumstances they are applied, so that total economic value, pricing, and net value to the customer are calculated appropriately;

- In clean up, look at the model as a whole to make sure its elements hang together and make sense.

Here are some common mistakes and gaps, taking these four steps in order.

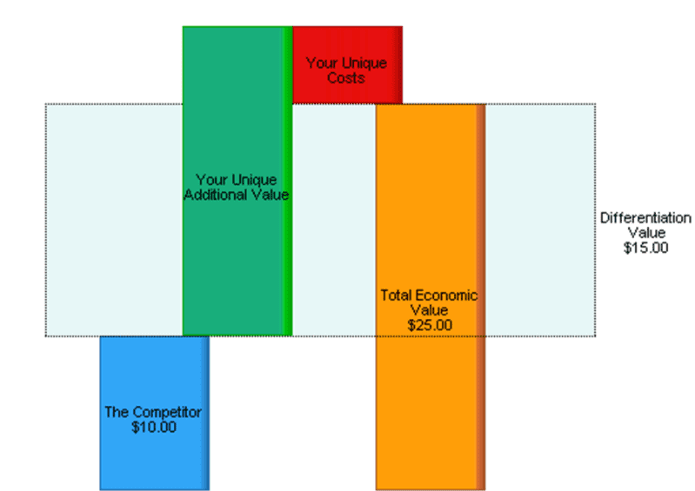

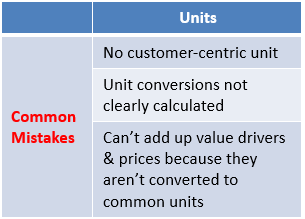

1. Frame the Comparisons. Any business case to buy needs to frame the value and price comparisons Our offering is being compared to a reference alternative for a specific customer segment. Before diving into a value model, a good coach obtains some market background by asking what our chosen customer segment is doing today. If the answer is unclear, perhaps this is because there are several possible answers. This usually means that the customer segment chosen for initial modeling may not be specific enough to obtain good value estimates.

1. Frame the Comparisons. Any business case to buy needs to frame the value and price comparisons Our offering is being compared to a reference alternative for a specific customer segment. Before diving into a value model, a good coach obtains some market background by asking what our chosen customer segment is doing today. If the answer is unclear, perhaps this is because there are several possible answers. This usually means that the customer segment chosen for initial modeling may not be specific enough to obtain good value estimates.

Understanding what the customer is doing today leads naturally to asking what choice our customer is most likely to make when they consider our offering. The reference alternative needs to be relevant for the customer we are considering. If it isn’t, we are wasting time quantifying value for this comparison.

Having identified a good reference alternative, we need to ask whether our offering is comparable to the reference alternative. Our offering may have multiple potential components. We need to be clear on which components are part of the solution we are considering. If our offering is poorly defined, value drivers compared to the reference alternative will be either confusing or mistaken.

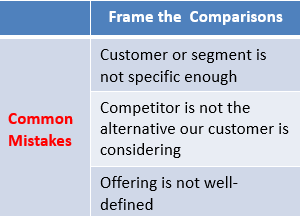

The potential gaps in our model follow naturally from the framing questions. As we clarify an initial customer segment for the model, we naturally identify other segments of interest. Frequently this segmentation includes customer types based on their business characteristics or their problems. Often we realize that a single buyer may consider more than one reference alternative as they consider a purchase – they may compare us to the status quo or to multiple competing offerings. Finally, the process of defining our initial offering helps identify other, potentially attractive, variants of our offering.

The potential gaps in our model follow naturally from the framing questions. As we clarify an initial customer segment for the model, we naturally identify other segments of interest. Frequently this segmentation includes customer types based on their business characteristics or their problems. Often we realize that a single buyer may consider more than one reference alternative as they consider a purchase – they may compare us to the status quo or to multiple competing offerings. Finally, the process of defining our initial offering helps identify other, potentially attractive, variants of our offering.

As a coach identifies gaps in how a model is framed, and as teams fill in the gaps, the model becomes more useful. Adding easy identification of customer segments, choices between multiple reference alternatives and choices between our potential offerings makes the model relevant to more and more customer circumstances.

Identified gaps in how a model is framed can also help highlight customer differences arising from the value chain downstream from our offering. Perhaps we started off considering large, vertically integrated customers for our product. As we tease out where value is realized in the chain, this helps to identify strategies that can address the less integrated parts of the value chain by enabling our immediate customers to capitalize on value realized by their customers.

Once we refine our initial price and value calculations, the next step is to work through the impact of segments and choices on: (i) price calculations, (ii) the relevance of value drivers, and (iii) the quantitative claims we make regarding the impact of switching to our offering. Filling in gaps helps refine our microsegmentation and our offering strategy, as we enhance the relevance and specificity of the content we provide to sales teams.

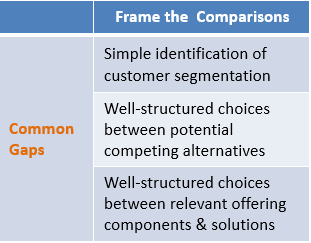

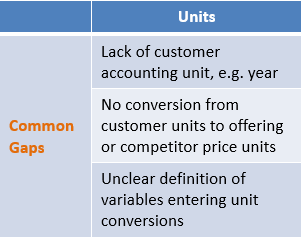

2. Units. Units make a difference. Math and graphs in a value model need to make sense. To add up value drivers and prices in a waterfall graph, or to add up costs in a TCO graph, the elements of those graphs need to be converted into the same unit.

2. Units. Units make a difference. Math and graphs in a value model need to make sense. To add up value drivers and prices in a waterfall graph, or to add up costs in a TCO graph, the elements of those graphs need to be converted into the same unit.

Miscalculation and confusion arise frequently when a model has no customer-centric unit. Too often value drivers are badly quantified when they are calculated based on offering units. Pricing expressed in product-centric units sometimes plays into the hands of procurement, highlighting sticker shock when there are acquisition efficiencies in buying our product. The lack of a customer-centric unit is one of the biggest mistakes teams make in their value models.

When there are one or more customer units, sometimes unit conversions are not clearly calculated. Clear, mathematically correct conversions between different customer units, and between offering units and customer units, help to translate results into terms that will resonate best both internally and with customer audiences.

Finally, value drivers and price components need to be readily converted into a common unit so that they can be summed up and compared. Adding them up in any other way produces non-sensible results.

Filling potential unit gaps in a value model makes the value model more useful. Even if we have customer units based on operating metrics, e.g. customer output, it always helps to include a customer accounting unit, e.g. year. When we see the value we create for a customer annualized, it helps us understand its potential importance to a buyer’s business and to identify stakeholders who will care. It also helps our buyer sponsor answer questions coming from their internal finance stakeholders.

Filling potential unit gaps in a value model makes the value model more useful. Even if we have customer units based on operating metrics, e.g. customer output, it always helps to include a customer accounting unit, e.g. year. When we see the value we create for a customer annualized, it helps us understand its potential importance to a buyer’s business and to identify stakeholders who will care. It also helps our buyer sponsor answer questions coming from their internal finance stakeholders.

Being able to convert results from customer units into offering and competitor price units helps us think about our product’s impact or value. Sometimes a significant innovation is underpriced because we haven’t understood the magnitude of its value when translated back to our price metric. Lastly, having clearly specified variables that enter into unit conversions helps to structure good discovery questions about customer scale and business operations.

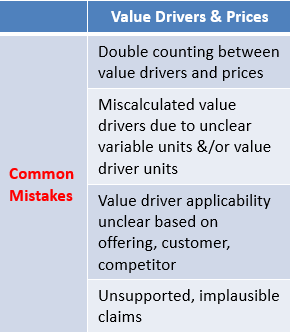

3. Value Drivers and Prices. Positive value drivers, negative value drivers, and prices should be well-quantified for a specific, well-defined offering, for a specific competing alternative, and for a specific customer segment.

3. Value Drivers and Prices. Positive value drivers, negative value drivers, and prices should be well-quantified for a specific, well-defined offering, for a specific competing alternative, and for a specific customer segment.

Check for double counting. If we have modeled a competitor price in a value waterfall, it is already in the model as a saving. Including that price as part of calculating a distinct value driver (e.g. inventory savings) makes sense, but including the entire competing price as a separate saving in a value driver is double counting.

In each value driver, look at how variables are defined and how the value driver is calculated. Unclear variable definitions and unclear value driver units often result in math mistakes.

Consider the context of our specific offering, competitor, and customer segment. Ask whether a value driver applies or not, and under what circumstances. If “it depends” is the answer, then ask “what does it depend on?” This helps identify further value-based segments, choices to make in the model, and good discovery questions to ask customers.

Finally, consider the claims that a value driver makes about our offering’s advantage. Are the claims plausible quantitatively in light of the value story and any anecdotes? Ask teams for support. Brainstorm with teams about where they might look, who they might ask, and what analogous situations might support hypotheses.

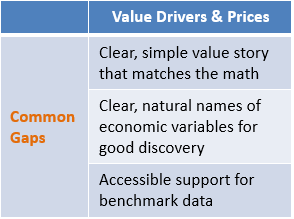

Then look for gaps. A good story and rationale should accompany each value driver. Make sure that the explanation matches the math. Help teams simplify the formulae and displays where possible. Economic variables that enter the model should have a natural name where their units are well-specified. If variables are clear and displayed appropriately, then discovery questions to customize the model for a buyer’s circumstances should come naturally. Lastly, make sure the team provides whatever support is available for benchmark data used in the value model. The data don’t have to be perfect but we should deploy what we have effectively. Good commercial teams continue to refine the quality of their data over time. Making support accessible helps to capitalize on an ever-improving information asset.

Then look for gaps. A good story and rationale should accompany each value driver. Make sure that the explanation matches the math. Help teams simplify the formulae and displays where possible. Economic variables that enter the model should have a natural name where their units are well-specified. If variables are clear and displayed appropriately, then discovery questions to customize the model for a buyer’s circumstances should come naturally. Lastly, make sure the team provides whatever support is available for benchmark data used in the value model. The data don’t have to be perfect but we should deploy what we have effectively. Good commercial teams continue to refine the quality of their data over time. Making support accessible helps to capitalize on an ever-improving information asset.

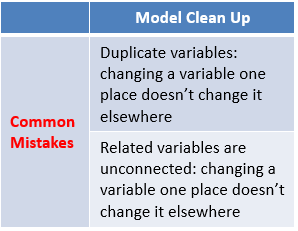

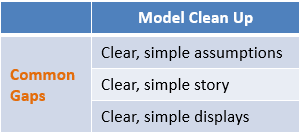

4. Model Clean Up. Having considered the detail of a model, it is always good to look at the model as a whole to see how it hangs together. One common model mistake occurs when there are duplicate variables when there should be just one. Changing the value of a variable one place should ripple all the way through the model. Another common mistake occurs when related variables are unconnected. For models to work effectively, changing a variable should flow through to other variables that are dependent on that variable.

4. Model Clean Up. Having considered the detail of a model, it is always good to look at the model as a whole to see how it hangs together. One common model mistake occurs when there are duplicate variables when there should be just one. Changing the value of a variable one place should ripple all the way through the model. Another common mistake occurs when related variables are unconnected. For models to work effectively, changing a variable should flow through to other variables that are dependent on that variable.

Value models naturally start simple and get more and more complex as teams identify sources of value and value-based segmentation. This content is useful in designing strategies but its complexity becomes a drawback in effective communication. Good value coaches are obsessive in their quest for simplicity. Get teams to present their model. Can we do without long lists of assumptions? Can we tell the story in a more readily understandable way? Are our displays intuitive enough that someone unfamiliar with the story could look at them and understand them? Good coaches get teams to test and refine their value propositions early and often by presenting them internally, as well as to friendly customers.

Value models naturally start simple and get more and more complex as teams identify sources of value and value-based segmentation. This content is useful in designing strategies but its complexity becomes a drawback in effective communication. Good value coaches are obsessive in their quest for simplicity. Get teams to present their model. Can we do without long lists of assumptions? Can we tell the story in a more readily understandable way? Are our displays intuitive enough that someone unfamiliar with the story could look at them and understand them? Good coaches get teams to test and refine their value propositions early and often by presenting them internally, as well as to friendly customers.

Coaching Effectiveness. As suggested earlier, not all experienced business professionals are open to coaching. Not all coaches have management authority over the professionals they coach. In the absence of top-down, command leverage, coaches often need to sell the value of their services to players, just to get players to engage and to be open to accepting a coach’s guidance.

A few simple principles apply in coaching experienced value players that apply in all coaching, or, for that matter, in most human professional interaction:

- Ask questions, avoid arguing. Leading a player to realize the right approach is more powerful and more sustainable than to dictate the right approach. The more insightful your questions, the more players will appreciate the value you bring in making them successful.

- Use other experiences and perspectives judiciously to persuade subtly and to motivate. As a coach, your aim is to move players toward better habits and better content, not to monopolize air time or prove you are the smartest person in the room. Your experience and your insights are helpful in measured doses.

- Respect the player’s knowledge. They may have good reason for resisting your insights or your guidance. Not everything you recommend makes sense or will be adopted. Despite your well-deserved confidence, coaches can still learn something.

- Encourage, avoid criticizing. Your objective is to make players successful. Building resentment won’t improve their coachability. Harsh criticism won’t build their self-confidence.

- Coach, avoid playing. It is often tempting to fix a problem in a model instead of helping a player do it. Fixing a problem yourself doesn’t get buy-in and doesn’t encourage the player to play better next time.

In sum, constructive, objective questions set the right tone for a coaching session.

Coach World Class Midfielders. Quantified customer value and prices are central to good midfield play on the B2B field. With high quality value content, our team is set up strategically for better pricing, positioning and go-to-market strategy. That value content feeds better Value Propositions which deliver better sales execution.

Coach World Class Midfielders. Quantified customer value and prices are central to good midfield play on the B2B field. With high quality value content, our team is set up strategically for better pricing, positioning and go-to-market strategy. That value content feeds better Value Propositions which deliver better sales execution.

Value coaches drive teams to be objective in quantifying value and prices. They invite teams to be creative in identifying segments, potential offerings, and possible changes in price metrics. They provide perspective, experience, and advice as commercial teams work harder to understand their customers. By understanding how our differentiated offering generates dollarized value, by comparing customer alternatives based on their financial outcomes, we come to understand both how to partner with new buyers and what it takes to deliver recurring results for loyal customers.

Looking at customers through a value lens nourishes value management as a commercial strategy and value communication as a sales habit. Value management drives strategic decisions aligned with sustainable customer success. Value Propositions provide core sales content to support sales team collaboration with customers by focusing on the business outcomes that buyers realize. Midfielders, quantifying value, build confidence in their offering by objectively assessing the competition and the customer. Players move the ball downfield to set up better shots on goal. More goals translate into sales growth and greater profitability.